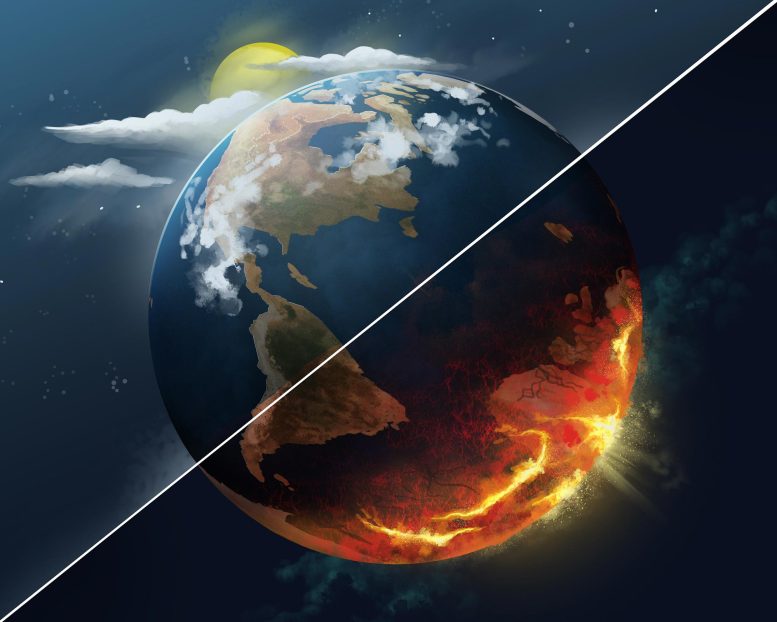

Researchers highlight the severe risks of destabilizing Earth’s tipping elements like ice sheets and ocean currents due to climate change, emphasizing the need to maintain the 1.5 °C limit set by the Paris Agreement to avoid dire future consequences. Failure to adhere to these limits increases the likelihood of tipping events, which are significant changes that could impact global climate stability for centuries.

Anthropogenic climate change could destabilize large-scale components of the Earth system such as ice sheets or ocean circulation patterns, the so-called tipping elements. While these components will not tip overnight, fundamental processes are put into motion unfolding over tens, hundreds, or thousands of years. These changes are of such a serious nature that they should be avoided at all costs, the researchers argue.

In their new study, published today (August 1) in Nature Communications, they assessed the risks of destabilization of at least one tipping element as a result of overshooting 1.5 °C. Their analysis shows how crucial it is for the state of the planet to adhere to the climate objectives of the Paris Agreement. It further emphasizes the legacy of today’s climate (in)action for centuries to millennia to come.

Assessing Tipping Risks Under Current Climate Policies

“While timescales to 2300 or beyond may seem far away, it is important to map out tipping risks to the best of our abilities. Our results show how vitally important it is to achieve and maintain net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in order to limit these risks for the next hundreds of years and beyond,“ explains co-lead author Tessa Möller, scientist at IIASA and PIK. “Our calculations reveal that following current policies until the end of this century would lead to a high tipping risk of 45 percent of at least one of the four elements tipping by 2300.”

Escalating Risks With Rising Global Temperatures

“We see an increase in tipping risk with every tenth of a degree of overshoot above 1.5 °C. But if we were to also surpass 2 °C of global warming, tipping risks would escalate even more rapidly. This is very concerning as scenarios that follow currently implemented climate policies are estimated to result in about 2.6 °C of global warming by the end of this century,” says Annika Ernest Högner from PIK, who co-led the study.

The Urgency of Achieving Net-Zero Emissions

“Our study confirms that tipping risks in response to overshoots can be minimized if warming is swiftly reversed. Such a reversal of global warming can only be achieved if greenhouse gas emissions reach at least net-zero by 2100. The results underline the importance of the Paris Agreement’s climate objectives to limit warming to well below 2 °C even in case of a temporary overshoot above 1.5 °C,“ says study author Nico Wunderling of PIK.

Importance of Limiting Global Warming to 1.5°C

The four tipping elements analyzed in the study are pivotal in regulating the stability of the Earth’s climate system. So far, complex Earth system models are not yet able to comprehensively simulate their non-linear behavior, feedbacks, and interactions between some of the tipping elements. Therefore, the researchers used a stylized Earth system model to represent the main characteristics and behavior and thereby systematically include relevant uncertainties in tipping elements and their interactions.

“This analysis of tipping point risks adds further support to the conclusion that we are underestimating risks, and need to now recognize that the legally binding objective in the Paris Agreement of holding global warming to ‘well below 2°C’, in reality means limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Due to insufficient emission reductions, we run an ever-increasing risk of a period overshooting this temperature limit, which we need to minimize at all costs, to reduce dire impacts to people across the world,” concludes PIK director and author of the study Johan Rockström.

Reference: “Achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions critical to limit climate tipping risks” by Tessa Möller, Annika Ernest Högner, Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, Samuel Bien, Niklas H. Kitzmann, Robin D. Lamboll, Joeri Rogelj, Jonathan F. Donges, Johan Rockström and Nico Wunderling, 1 August 2024, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-49863-0

2 Comments

That’s just a load of hogwash. There won’t be a “tipping point” and we’re not turning into Venus 2.0. That’s not possible because we’re much further away from the Sun than Venus. The Sun just doesn’t have that kind of power over here.

The Earth has been through much warmer periods and through much colder periods. Yet there never was any runaway event these fools are suggesting. The effects of the “greenhouse gases” have been severely overstated in all their climate models and the corrective factors of the complex system that is our climate have been ignored and some are not even known. Even the articles on this stupid website acknowledge this every once in a while.

So why do you keep on with this fearmongering? We’re not doing away with fossil fuels anytime soon. We can’t and we shouldn’t.

“… following current policies this century would commit to a 45% tipping risk by 2300 (median, 10–90% range: 23–71%), …”

That is somewhat less than the typical +/-~2-sigma, 5-95% probability range, which would be closer to a range of 20-80% tipping risk. Would you risk a lot of money on an investment if your financial adviser told you that your returns had a 95% probability of being as much as 30% higher or LOWER than the forecast return? The actual article speaks to the modeling problem of “a lack of processes important for resolving tipping.” In that light, how were the nominal percentage and uncertainty range estimated? Apparently, they used a Monte Carlo ensemble and derived their numbers from the runs that exhibited at least one of the four tipping parameters transitioning. The only problem with this is the unstated assumption that the model they used is reliable.

Again from the article, it says, “This can be explained by the fact that the tipping threshold ranges for the ice sheets begin well below 1.5 °C2. It is unclear to me what is meant by that. Ice melts at a fixed temperature. For a runaway situation, the rate of increase of the elevation of the melt-line would have to exceed the lapse rate. That is to say, no ice will melt until it reaches the melting point, and the temperature drops more rapidly with elevation than can be expected to occur at sea level over a mid-time interval. That is to say, the high elevation glaciers in West Antarctica are unlikely to be affected significantly by a 2 or 3 degree warming at sea level when the Winter high-elevation temperatures are as much as -50 deg C (recently nearly -80 deg C).

Why are the error bars for the mid-term tipping risk (next 300 years) substantially the same as the error bars for the long-term (next 50,000 years)? The implication is that the distant future can be predicted with essentially the same accuracy as the next 275 years. I don’t think that is a reasonable assumption. I would expect that the uncertainty would be at least proportional to the amount of time, if not much greater.